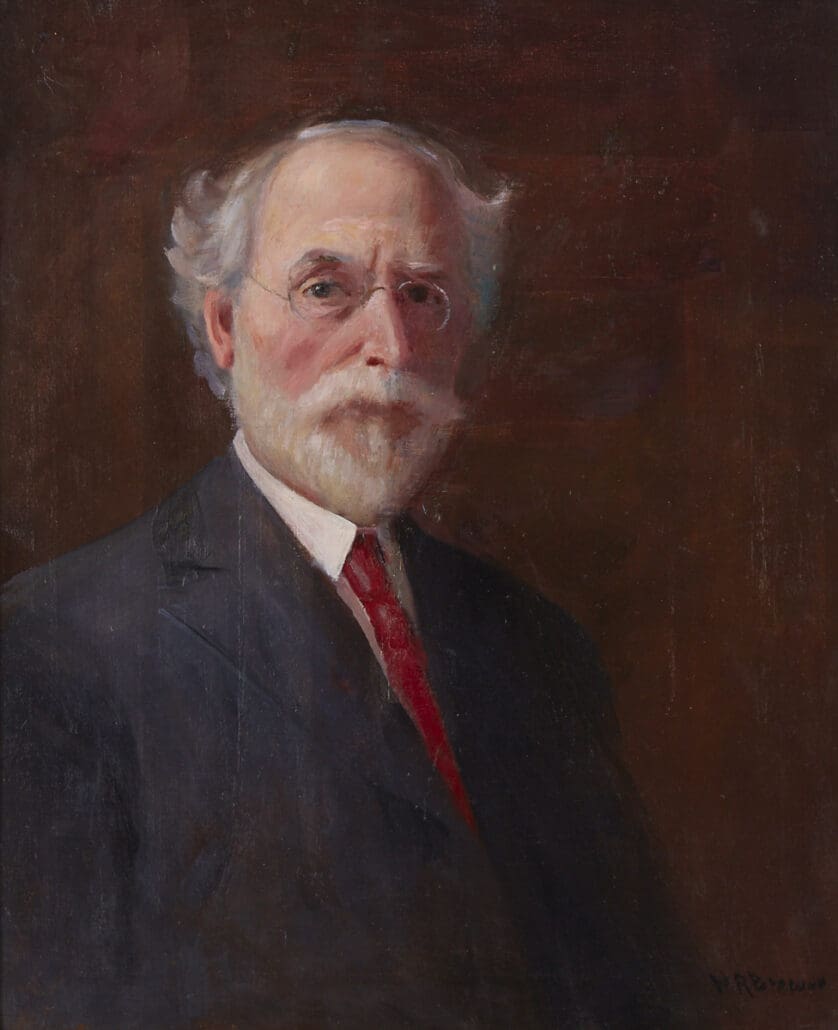

Self-Portrait

This self-portrait, one of several Nicholas Brewer painted, depicts the artist as an old man. He looks distinguished, not unlike the many influential businessmen and politicians–including Franklin Delano Roosevelt–he painted during his career. His dark suit speaks to the somber respectability he aspired to–and briefly achieved–but his wild hair provides a hint about his artistic personality. Portraiture is how Brewer made his living for most of his adult life, and his mastery of the style is evident in this painting. Brewer believed that as a portraitist it was his job to capture not only the subject’s physical likeness, but also some aspect of their true being or personality. In this work, Brewer peers at the viewer through his glasses, looking a little suspicious or even stern. However, there is a hint of a smile around his cheeks, barely visible through his whiskers, that suggests the sense of humor so evident in his autobiography. In his autobiography, he says of portraits: “Apart from the generally pleasing likeness there must be an expression of the artist–his conception and description of the character of the subject. If it is that, it is a creative thing and a real work of art[.]” This, then, is a real work of art in Brewer’s eyes, showing us not only his features but who he thought he was–respectable, observant, and a bit amused by the world around him.

Fort Snelling

It is rare for one of Nicholas Brewers’ works to depict a specific place–he typically preferred to create idealized amalgamations of the scenes instead of faithful renderings. The fact, then, that Fort Snelling is so clearly recognizable speaks to how important the fort was to Nicholas Brewer. Fort Snelling, one of Minnesota’s most iconic landmarks, was built in 1820 in an effort to keep the British out of the Northwest and from encroaching on the American fur trade, and later played an important role in the US-Dakota War of 1862 and its aftermath. By the time this painting was executed in the 1890s, Fort Snelling was a picturesque ruin. Brewer felt a deep personal affinity for Minnesota history and the fort itself, and when he opened his art school in St. Paul in 1888 he would frequently take students to Fort Snelling and nearby Pike Island to paint. More personally for Brewer, he spent his wedding night on Pike Island, and, when discussing this in his autobiography, takes the time to discuss the history of the fort.

This painting is delicately executed, faithful to the scene it depicts. The river winds away in the background, dully gleaming in the hazy Minnesota sunset. The last of the light from the falling sun highlights the sides of the tower and the tops of the surrounding trees, which closely embrace the tower, giving it the effect of emerging from the land that surrounds it. The stones of the tower are highly textured, as is some of the surrounding flora, causing the focal point of the painting to physically stand out against the background, which fades away into the sunset. It is a romantic depiction of the fort, with the falling sun paralleling the decline of the fort, both gaining in beauty as they lessen in power.

Bountiful Harvest

Bountiful Harvest gives a lovely autumnal twist to traditional still life themes, as well as providing an illustration of Brewer’s agrarian background. He grew up on a farm in Southern Minnesota, and later lived with his family on a farm in Stacy, Minnesota, from 1893 to 1898, where he found much inspiration for his art. Brewer loved the simple, hard-earned pleasures of a farming life, and this painting captures that. The luscious fruit is gathered together as if freshly harvested, a happy reward for a season’s hard work.

While still lifes are uncommon in Brewer’s oeuvre, this well-executed example shows that Brewer had a deep understanding of the genre. He nods to many common still life tropes, while transforming the overall scene into something that is personal to his own life. Fruit has long been a mainstay of still life as a genre; however, instead of the fine, exotic fruits favored in most quintessential still lifes, Brewer chose apples, pumpkins, grapes, and pears, all produce that would grow on a Minnesota farm such as Brewer’s own. He shows the fruit gracefully overflowing and tumbling out of its receptacles–but these, instead of the standard gleaming silver bowls, are humble baskets. The dying autumn leaves forming the background of the painting are a clever reference to the memento mori frequently present in traditional still lifes; however, in conjunction with the harvest fruit, they add to the feeling of autumnal cheer. This is a still life, but it is a very Brewer still life, emphasizing his fundamentally pastoral aesthetics and values.

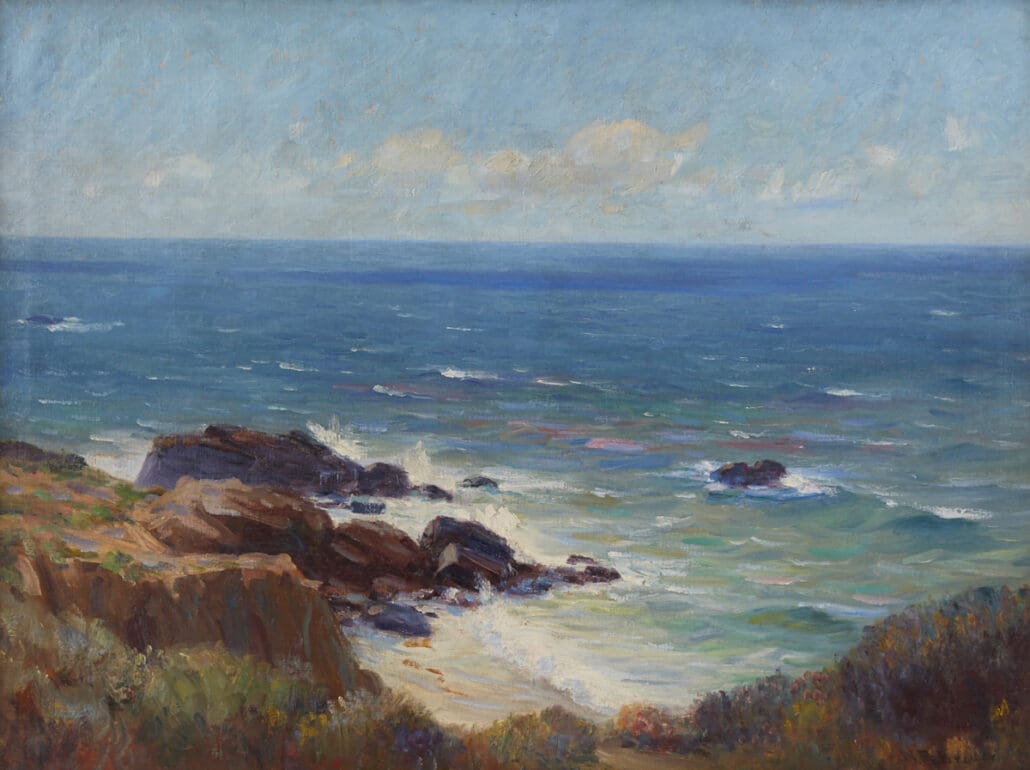

Off Laguna

During his 1921 trip to California, Nicholas Brewer made friends with a number of fellow artists working there, whom he found delightfully open and welcoming. Among these were Jack Smith (1873-1949), best known for his landscapes and seascapes of the American west. Smith invited Brewer to come stay with him in Laguna Beach, where they spent several weeks painting what Brewer calls in his autobiography “the marvelous coast with its rocky cliffs.”

Off Laguna is widely recognized as one of Nicholas Brewer’s finest seascapes. It perfectly captures the buoyant excitement of his trip to California, with the whitecaps of the gentle waves jumping and splashing on the rocks. The vista, framed by the rocky shore, exemplifies the multitude of vibrant blues of the coast, with the bright pale sky fading into the dark blue of the deep ocean, which in turn lightens to clear turquoise as it moves to touch the sand. The mesmerising waters show glints of other colors, with shell pink, peach, and gold making what seem to be fleeting appearances on the rolling waves. On land, the scrubby California wildflowers, so different from verdant Minnesota flora, have been rendered by Brewer in meticulous detail. The pinprick gems of color stand out from the dusty brown and green foliage, but blend at a distance, creating lovely washes of color that mirror the twinkling sea. There is the hint of a path along the lower left, inviting the viewer to come take a dip in this appealing Pacific cove. It is easy to imagine that Brewer, after sketching this scene, made his way down this path to revel in the surf at his good fortune in being under the joyful California sun.

On the Beach

On the Beach, like Off Laguna, depicts the shore around Laguna Beach. It is painted on a much smaller scale than Off Laguna, and provides a more Impressionistic depiction of the beach. The landscape is rendered in swift, sweeping brush strokes, providing an impression of the movement of the scene, from the waves out to sea to the calm water in the small inlet depicted. The jagged rocks are made up of highly textured layers of paint, and the texture of the pebbly beach is evident in the thicker deposits of paint along the water’s edge. Thin strokes of green around the rocks and the water suggest clumps of slick seaweed washed up on the shore. The viewer can almost feel the texture of the beach under their feet just by looking at the painting.

The sense of intimacy in the painting, encouraged by its scale, is strengthened by the composition. The composition also contributes to the calm solitude: the small pool, tightly framed by expanding semicircles of craggy rock, feels hidden from the outside world. Coupled with the lack of figures, a characteristic aspect of Brewer’s landscapes, it creates the feeling of having stumbled upon a secret cove, exclusively shared by painter and viewer.

Aliso Canyon, California

During Brewer’s visit to Laguna Beach with Jack Smith and his fellow artist friends, they made several trips to Aliso Canyon in the San Joaquin Hills. It is clear that Brewer was impressed by the grandiosity of the canyon. His choice of vantage point for this painting–positioned at the bottom of the canyon, looking up–emphasizes the tremendous size of the canyon. Positioning the viewer within the landscape in such a tangible way enables the viewer to experience the wonder Brewer must have felt being dwarfed by this geological landmark. The grove of trees in the lower left of the composition provide scale, further reinforcing how small a visitor to the land must feel.

The influence of Brewer’s new friend and fellow artist William Wendt (1865-1946) is evident in the way Brewer captures the form of the land. Wendt is best known for his preoccupation with the land itself, through its geographic features and topography. This attitude is noticeable in Brewer’s handling of the canyon. The texture and outcrops in the rocky walls of the canyon are highlighted with sun and shade, and emphasized with pastel-colored patches of wildflowers. The thick impasto used on these flowered areas further accentuates the bouldered surface of the canyon walls. The creek flows along the base of the canyon, so subtly rendered it is barely noticeable save for the area of reflecting sunlight just downstream from the trees. The creek itself primarily serves as a border for the canyon, once again drawing attention to the topography by providing contrast to the curves and caves along the bottom of the cliff wall.

In 1922, Aliso Canyon, California was exhibited at the Decatur Institute of Civic Arts in Decatur, Illinois, as part of a Brewer solo exhibition. The Institute then purchased the painting for its permanent collection. A contemporary newspaper article in The Decatur Herald discussing the sale provided a glowing review of the piece: “The Aliso Canyon [Aliso Canyon, California] is looked upon as the best painting in the collection shown by Mr. Brewer and he was frankly rather loath to sell it. […] It was painted by Mr. Brewer when he was in California last summer and carries in it not only the distance and coloring but seemingly also the very atmosphere of that land of sunshine.” It was later included in “The Art of Nicholas Richard Brewer,” an exhibition put on by the Gallery of the Woman’s College Library at Duke University, Durham, North Carolina, from April 7 to 21, 1932.

San Joaquin Hills

San Joaquin Hills, like Aliso Canyon, California, was painted in the hills around Laguna Beach. However, it depicts a more humble view of the hills, with the larger ridge a blur in the background, and the foreground a rolling hill dotted with trees that would not look out of place in the midwest. While the impression of scale is somewhat muted, the colors are far from it. The grass on the hillside is a bright, electric green, and the ridge in the background is a mass of vivid teal and indigo with highlights in a dusty pink that reflects the pink of the skies.

This painting is notable among Brewer’s work for its strong sense of temporality. The clouds are rolling in over the hills, as if a storm is about to start, and the tree in the foreground appears to bend slightly in the wind. The viewer is left with the impression that this bright, sunny landscape will shortly be altered into something quite different. The sketchy nature of the painting adds to the impression that it depicts a definite moment in time, an unusual quality in a Brewer painting. Certainly it is possible that this was a sketch painted en plein air, as Brewer created many sketches while outdoors sightseeing during his time in California. Regardless of whether it was painted from a scene in front of Brewer, or one reconstructed later in a studio, it perfectly captures the mood of a bright hillside, and the fleeting bliss of Brewer’s trip to California.

This rare genre painting, on a subject long cherished by artists, was painted as Nicholas Brewer was becoming established in his career. It is a rather surprising choice of subject matter for Brewer, who tended to depict women only at their most proper and pious. This painting, by contrast, is intimate and perhaps even a little provocative. The morning light coming in through the gauzy curtain visible in the mirror caresses the figure’s exposed back. Her pale green shawl has slipped off one shoulder and gathered in the crook of her elbow as she concentrates on affixing a flower, freshly plucked from the vase on her vanity, into her hair. The top drawer of her dresser is open, and some delicate, probably unmentionable, garment dangles out.

The atypical subject matter also provides a venue for Brewer to show off his technical expertise. Much of Brewer’s portraiture is fairly austere, with very few examples of the types of delicate, flowing fabrics depicted in this work. Here, the focus is on the fabrics. Brewer pays great attention to the way the figure’s shawl drapes and folds, and he portrays the fabric’s silky texture through expert use of light and shadow. The dainty lace along the edge of the shawl is subtly rendered, adding to the soft sensuality of the scene. It is a painting both tender and technical, displaying Brewer’s mastery of both the mechanics and emotions of painting.

Texas Hill Country

During Nicholas Brewer’s many trips to the west, one of the things that impressed him most was the colors he saw there, how vibrant the sky, the ground, and the mountains were. Nowhere is the power of this impression more evident than in Texas Hill Country. This painting brilliantly captures the rich reds of the rocky Texas soil, the succulent blue-green of the cacti clustered along the ground, dotted with bright tangerine flowers that seem almost to glow against their shadowy background. The muted trees provide a foil to the vividity of the rest of the scene, framing a path that appears to lead to the distant hills, looming majestically in lilac-tinged green under the expansive and cloudless azure sky.

This painting, like many of Brewer’s most powerful works, is a love story to the landscape of the American west. His awe at the new scenery he was experiencing is palpable in every careful brushstroke. He captures the breathtaking magnitude of the landscape, but he frames it in a way that makes it welcoming instead of intimidating. The shadowed foreground beckons the viewer’s eye forward in the sunlight, to linger on the bright golden plain, and onward up to the softly rendered, comforting hills.

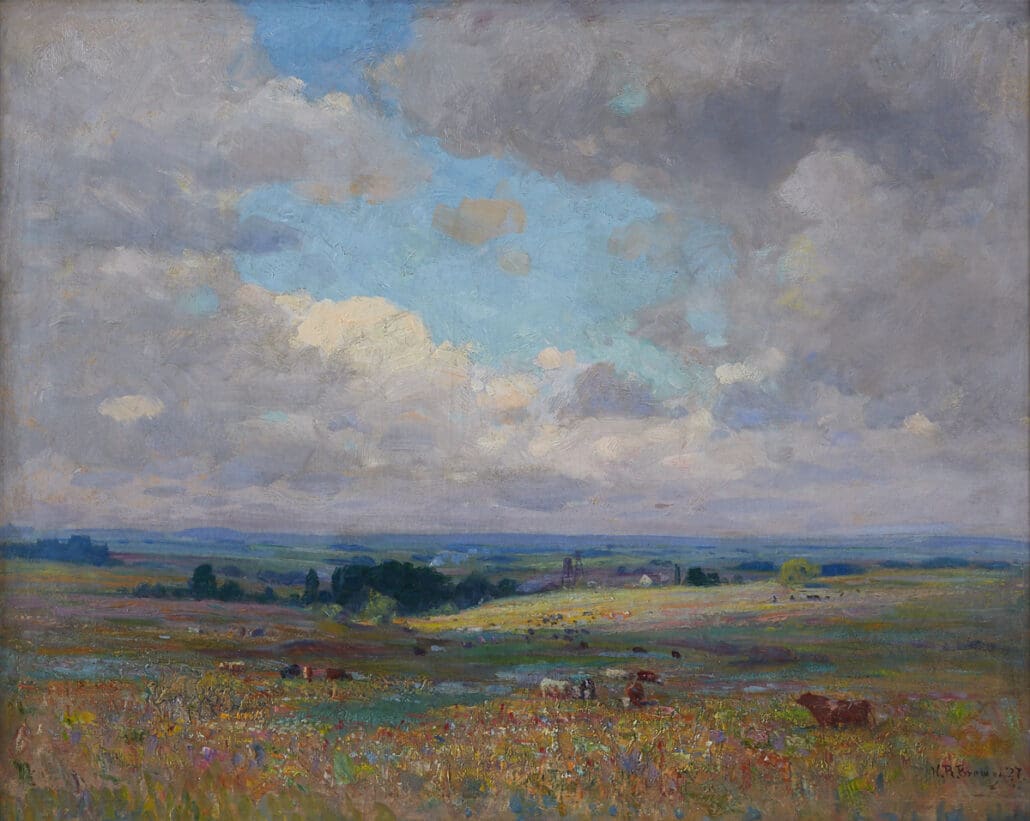

Pastoral Scene

Pastoral Scene captures Nicholas Brewer’s joy in the rolling expanses of Texas prairie. The land stretches unobstructed to kiss the periwinkle-clouded sky at the far distant horizon. A multitude of brightly colored wildflowers and grasses appear almost to ripple in a breeze, their texture palpable in the heavy impasto in the foreground. Cattle graze in the middle distance, serene and unobtrusive. They are as much a part of the landscape as the low, rolling hills, easy to miss when viewed from a distance. Further back, nestled behind the crest of a hill, is a farm, the structures faint against the plains. The farm, much like the cattle, is painted in such a way that it seems a natural feature of the landscape, harmoniously blending with, rather than standing out from, the surrounding land.

The work is as much a skyscape as a landscape: the sky extends over two thirds of the canvas, mirroring and underscoring the vastness of the plains below. The masses of cloud are a significant presence, more topographical than the low hills below. Their height is conveyed through the many shades of gray, with the few sunlit tops of the clouds visible in striking contrast to the deep grays of the undersides. The sky and ground are not depicted as two separate elements: their interaction, shown in the broad dappling of sunlight on the fields, is vital to the composition. In capturing the marriage of the two vistas, Brewer captures both serenity and the joy in the wide open spaces.

Interested in these paintings?

Learn more about the show here.

See the paintings available for purchase here.