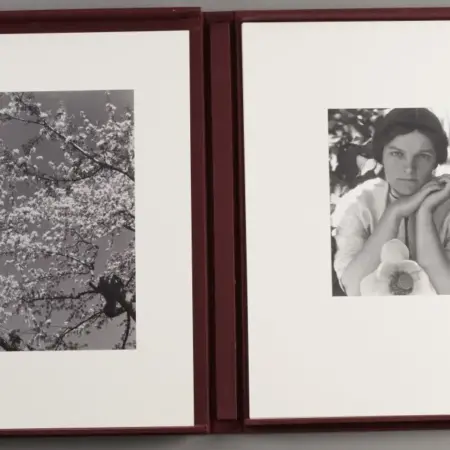

Edward Steichen

American Artist

1879-1973

Interested in selling a piece by Edward Steichen?

We have received top dollar for Edward Steichen works. Auction is the best way to quickly and transparently get maximum dollar for your artwork.

About Edward Steichen

Edward Steichen was one of the fathers of American photography, both artistic and commercial. Born in Luxembourg, Steichen’s family immigrated to the United States when he was two years old. Eventually, the family ended up in Milwaukee, where the young Steichen was an apprentice with a lithographic firm. He soon turned his interests to painting and photography, deciding in 1900 to travel to Paris to study and immerse himself in art. He stopped in New York on his way to Europe, where he sought out Alfred Stieglitz, the vice-president of the Camera Club of New York and a leading figure in American art photography. Stieglitz was impressed with his work and bought several pieces. The two created the basis for what would become a long and productive working relationship before Steichen left for Europe. Steichen spent two years in Paris, during which he shifted his interests almost entirely to photography, learning new cutting-edge methods for taking and developing photographs. During this time, Steichen made his mark as a portrait photographer, but he was also exposed to the French art scene. When Steichen returned to the US, he immediately rose to the top of the art photography scene. He joined Stieglitz’s new group, the Photo-Secession, through which many of his photographs were published and his work was displayed in many exhibitions.

His photography style at this time was painterly, fitting perfectly the Photo-Secession’s goal of establishing photography as a fine art. He returned to Paris in 1907, where he continued to learn new photographic techniques, but also was active in the art scene, fostering friendships with artists such as Auguste Rodin. When World War I began, Steichen was quick to volunteer. During the war, Steichen worked taking photographs from planes, furthering his already developing interest in the technical side of photography. In his early art photographs, he had striven towards a soft and foggy style, sometimes even kicking his camera stand while taking photographs to achieve a blurred effect.

During the war, however, he had to learn to do the opposite, trying to take the clearest photographs possible from the unsteady surface of an airplane. He had to add a new level of technicality to his photography, and this technicality is something that stuck with him after the war, shifting his style to be much clearer and more realistic. The war had another major effect on Steichen’s life: it effectively ended his friendship with Stieglitz, who did not share Steichen’s fervent patriotism and retained some loyalty to Germany, his home country.

This was the last nail in the coffin for their already strained relationship: Stieglitz resented Steichen’s growing interest in commercial photography, which Stieglitz saw as a betrayal of the artistic ideals they had shared in the Photo-Secession, a group which Steichen, in turn, felt that was increasingly a self-centered project for Stieglitz. After the war, Steichen turned his interests almost entirely to commercial photography. He did advertising photography and magazine spreads, taking portraits of the most famous and important people at the time for publications such as Vogue and Vanity Fair. He became hugely successful, defining the stars of the generation through his characteristic portraiture and innovating fields such as fashion and advertising photography. While he claimed to be past his former artistic aspirations, his artistic background clearly helped him to look at things differently and create new standards for photography. His studio drew important and famous clients until he closed it in 1938. After the closing of his studio, he went on to be a lieutenant commander for the U.S. Navy during World War II, documenting the war in the Pacific theater. He then went on to be a curator of photography for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, eventually becoming the head of that department, making a triumphant return to the art world to round out his career.