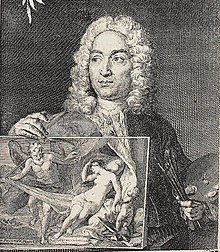

Joseph Anton von Prenner

Austrian Artist

1683-1761

Interested in selling a piece by Joseph Anton von Prenner?

We have received top dollar for Joseph Anton von Prenner works. Auction is the best way to quickly and transparently get maximum dollar for your artwork.

Joseph Anton von Prenner

A group of old, haglike women crowd around a steaming cauldron. The smoke rises up in a thick plume, enveloping several figures, who are flying away from the crowd, clearly intent on wreaking havoc. The crowd below revels, brandishing brooms, consulting grimoires, and even riding a skeleton. This image, which comes to us in Joseph Anton von Prenner’s 1728 engraving, seems comfortably fantastical. At the time of the image’s initial creation, however, it would have been interpreted as an illustration of a genuine phenomenon.

In the 16th century, fear of witchcraft gripped Europe. Witch-hunting began flourishing in Central Europe in the 15th century, and spread and intensified through Europe over the course of the next two centuries, peaking in the 17th century. Although the definition of “witch” was often blurry, witches were people who committed maleficia, or acts of ill-intentioned magic, and, more importantly to the church and political establishment, were in league with the devil.Witches were said to engage in many wicked activities, but the most alarming was the witches’ sabbath, in which witches met by moonlight–often traveling to distant locations by flying–to drink, dance, and make merry. Satan was generally present at these gatherings, collecting souls and giving demonic sermons in a mockery of Christian church services. Other common activities recorded included orgies, eating babies, and, of course, working magic of the most evil kind.

Witches’ sabbaths, in all their titillating detail, quickly became popular subjects for art during the period of witch trials. Woodcuts depicting witches and their sabbaths were distributed widely in broadsheets and pamphlets to the common people, but witches and their demonic activities also became popular subjects for painters and other artists. Interest in–and fear of–witches crossed class lines, with everyone from paupers to kings consuming tales and depictions of witchcraft. The witches’ sabbath scene described above comes from a painting from the mid to late 16th century. Two versions of this painting, which is known as Witches’ Sabbath, survive, done in oil on panel and differing slightly in size. Little is known about the creation of this painting. It is attributed to either Frans Verbeeck or Bartholomeus Spranger, two accomplished Flemish painters from the mid to late 16th century. It is unknown who initially commissioned the painting, but it is clear that one version of this painting made its way into the collection of the Imperial Gallery in Vienna at some point in its early life.

At this time–long before public museums and other public institutions–art had a very limited audience. Royalty and nobility amassed enormous collections of art, specimens, and other precious objects and curiosities, emphasizing their roles as the holders of knowledge and power within their kingdoms. These collections grew haphazardly at the whims of their owners and encompassed a wide variety of objects. By the 18th century, these collections were truly impressive, spanning archaeology, natural history, and art of all varieties, but they were accessible to only a lucky few. By the 1720s, however, this was beginning to change. Public museums began to open around this time, and these private collections began to be recorded in more lasting and accessible ways. At the Imperial Collection in Vienna, Frans van Stampart, the court painter, and Joseph Anton von Prenner, another accomplished artist, decided to immortalize the collection by creating engravings of each of the pieces in the collection in thirty volumes. Only three volumes were ever produced, and were published under the title Theatrum Artis Pictoriae between 1728 and 1733.

While van Stampart and von Prenner’s ambitious project was never completed, one of the paintings which was recorded was Witches’ Sabbath. Its inclusion in Theatrum Artis Pictoriae makes it a notable player in a different movement in history than the dark one it depicts–the movement toward popularization of knowledge. This engraving is so much more than the simple fantasy scene it appears to be on the surface. Instead, its history traces changing mindsets through central European history, showing the genuine fear of the dark arts during a period of witch panic, the hidden gems in a royal collection, and the early efforts to document and share carefully stored information with the public.