Louise Nevelson

American Artist

1899-1988

Interested in selling a piece by Louise Nevelson?

We have received top dollar for Louise Nevelson works. Auction is the best way to quickly and transparently get maximum dollar for your artwork.

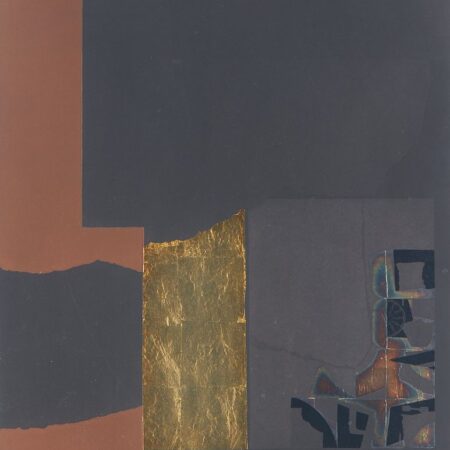

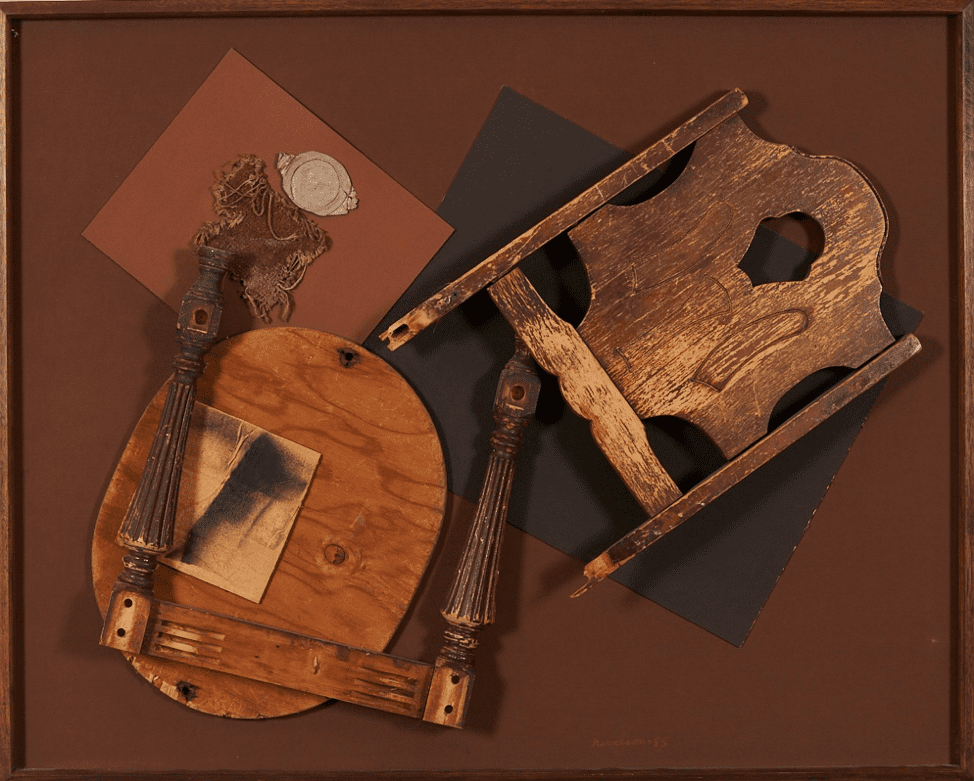

Louise Nevelson, Volcanic Magic XVII, available in Fine and Decorative Arts on March 30, 2019, 10 AM CDT.

About Louise Nevelson

“I feel what people call by the word scavenger is really a resurrection. You’re taking a discarded, beat-up piece that was no use to anyone and you place it in a position where it goes to beautiful places: museums, libraries, universities, big private houses… These pieces of wood have a history and drama… and someone comes along who sees how to take these beings and transform them into total being”.

–Louise Nevelson, Dawns and Dusks

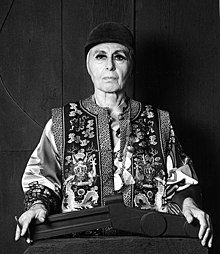

Louise Nevelson was a powerhouse of modernist sculpture. Her bold constructions using found objects shook the art world, as did her often scandalous, larger than life persona. Her work was cutting-edge during her lifetime and remains relevant, her unique approach to storytelling and her breathtaking, gothic silhouettes as fascinating to modern viewers as they were to her contemporaries.

Louise Nevelson was born to a poor Jewish family in Kiev in what was then the Russian Empire in 1899, but immigrated to the United States with her family in 1901. The family settled in Rockland, Maine, where her father ran a lumberyard. She often played with the scraps as a child, taking an early interest in sculpture. In school, she had no aptitude for academics, but excelled in her art classes, and enjoyed creating whimsical clothing for herself, constructing hats and other items.

When she was eighteen, she was introduced to Charles Nevelson, a wealthy New Yorker, by his brother Bernard, with whom she had become friends when his work in the shipping business had taken him to Rockland. They married in 1918, and she moved to New York City. She was immediately enraptured by the city, and took full advantage of the opportunities it offered to a young woman with a thirst to learn: she took acting and music classes, attended concerts and lectures, and visited museums. Despite her love for her new home, Nevelson found herself very unhappy in her marriage, particularly after the birth of her son. She found escape in visiting museums, where she was inspired by things as diverse as Japanese Noh theater costumes and cubist artworks, and by attending art classes at the Art Students League.

Finally, in 1931, she left her husband and traveled to Munich to study with Hans Hofmann. Cubism as he taught it resonated with Nevelson, and had a major effect on shaping her later work. In her words, “[i]f you read my work, no matter what it is, it still has that stamp. The box is a cube.” After traveling for a few more months, she returned to the United States to be with her family, but soon returned to Europe, eager to learn more in the art schools of Paris. After a brief stay there, she returned to the United States and the Art Students League. She soon met Diego Rivera, and began working as an assistant to him. She continued to take every opportunity to expand her art horizons, even taking up modern dance as part of her ongoing fascination with space and how space is occupied.

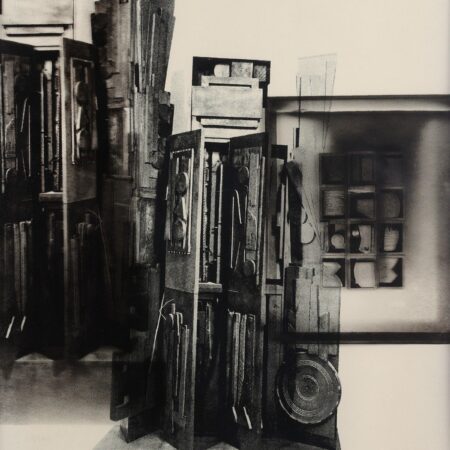

In 1941, Nevelson had her first show at Nierendorf Gallery, marking her breakthrough in the fine art world. She displayed sculptures created from boxes, leveraging her Cubist roots and obsession with space into something entirely new. She began receiving critical recognition, and continued expanding her work, moving literally outside the box. Around this time, Nevelson first began working with found objects. She felt that found objects already had stories of their own to tell, and assembling them as she was allowed her to contribute to those stories, and to keep the stories of discarded objects alive in a powerful way. While the way she manipulated these objects in her sculptures varied significantly throughout her career, their presence remained a constant.

In the mid-1940s, she began exhibiting her work regularly, and her success continued from there. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, her work was purchased by major museums, and she began receiving commissions to create the kinds of found-object sculptures for which she had become well known. These iconic sculptures were dark, monochromatic spires, disguising and making majestic the most mundane of objects. She was often grouped in exhibitions with the most influential artists of her time. Through the 1970s and 1980s, she received numerous honorary degrees and even had several books published on her.

She continued working and experimenting until her death in 1988, pushing the boundaries of color, texture, and form. She continued to try new sculptural media—though always admitting that wood was her favorite—along with making prints, designing costumes, and writing poetry. Volcanic Magic XVII, featured in Fine and Decorative Arts on March 30, 2019, was part of one of the final series Nevelson made, and in many ways shows a rounding out of her career as an artist. This piece displays several of the most quintessential Nevelson elements: found objects, surprising textures, and a usage of space both carefree and confrontational. However, it shows less typical elements as well. It is not monochromatic , but instead a gradation of color, showing depth through shades of brown instead of though the massive forms of her earlier work. It is in some ways a flattened version of her classic box constructions, with the exaggerated frame serving as the sides of a simple wooden box, the kind she often favored. This piece shows Nevelson continuing her lifelong exploration of space in a subtle, sophisticated direction, creating the illusion of space rather than creating ways to occupy it.

Volcanic Magic XVII includes an intriguing variety of found objects including the separated back and legs of a chair, a wooden oval, and fragments of paper, fabric, and a can. The chair back is well worn, with use-roughened edges and a mottled finish from loss of varnish—it is clear it has the kind of history Nevelson liked so well. The placement of the chair legs causes the viewer to wonder whether these had once been part of the same chair, which had been dropped on to the frame, breaking in the process. Volcanic Magic XVII constantly brings these questions to the viewer’s mind, involving them in the story, spinning new possible scenarios to connect these seemingly unrelated objects—is it a table setting, spinning in a cyclone? This is the true power in this work—Nevelson has chosen objects just right to keep their story continuing and changing, being speculated on and expanded upon by each viewer.